As the weather warms up aphid populations are becoming more obvious in crops. With aphid populations more visible in the crop, the key questions are whether they will impact on the yield of the crop, and whether it is necessary to control the aphids to avoid yield loss.

Aphid infestations are widespread this year in both barley and wheat. In some instances, the absence of rain through August, and large infestations that established early have resulted in visible honeydew on leaves – something we don’t see very often.

In response to the question of how to decide if and when aphid control is warranted – the available information does not provide a clear, consistent answer.

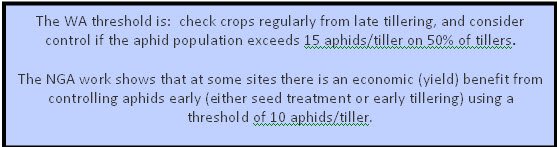

There are no economic thresholds (taking into account current costs of control and crop value), but there are thresholds suggested from work in WA and by the Northern Grower Alliance.

Queensland DAFF has conducted a number of field and glasshouse trials over the past 4 seasons, but we have not been able to get consistent yield loss in trials that tested a range of aphid infestations at different stages of crop development.

Making a decision about if and when controlling aphids is necessary?

The stage of crop development is a key factor in the decision to control or not.

If the crop is at, or close to booting (Z 3 7+), then you will start to see a rapid natural decline in the aphid populations.

The corn aphid colonises the tops of the plants, particularly the whorl. This species tends to disappear as the crop starts to boot and come into head.

The oat aphid which colonises the lower leaves and base of the plant declines in number as the quality of the plant changes from vegetative to reproductive. The plant be comes a less suitable host.

The other important factor in the natural decline in aphid populations is the activity of natural enemies (beneficial insects) like the parasitoid wasps, ladybirds and hoverflies. The combination of increasing natural enemy activity and the declining suitability of the crop for aphids often results in the aphid population crashing.

Most spraying for aphids occurs as the populations are peaking and just before the natural decline occurs. Spraying at this stage of crop development will have limited benefit in terms of protecting yield.

If the crop is still tillering, then the aphids have the potential to continue to build in number and exert stress on the crop. The longer an aphid population is present in a crop, the greater the potential impact on development and yield. Essentially the aphids divert carbohydrates, that the plant would otherwise store for use during grainfill.

Treating a large and growing aphid population in a tillering crop is probably the one time when you have the opportunity to reduce impact on yield. The earlier a crop is treated for aphids, the more time there is for survivors, or new immigrants, to establish in the crop. Selecting a product that minimises disruption to natural enemies is particularly important to avoid the possibility of a further infestation before the crop becomes unsuitable.

The picture below shows the impact of an early infestation of aphids (mixture of corn and oat) on plants in a glasshouse trial this season. The plants on the left were infested at Z12 and populations have built up (over 50 per tiller) and persisted for 6 weeks. The plants on the right were planted at the same time, but not infested until Z24 (about 4 weeks later). The aphids have retarded the growth of the early infested plants significantly, but had little impact on the later infested plants.

The development and impact of aphid infestations in northern hemisphere crops

Information from North America andEuropeindicates that there can be significant differences in the way different cultivars respond to the impact of aphids. Aphid populations in the northern hemisphere persist for longer, infesting developing heads and have a direct impact on grain fill. It is difficult to extrapolate directly from the northern hemisphere to our conditions.

Early aphid infestations (from seedling)

Root and shoot growth may be impaired as a result of aphids competing for N. Inadequate N for the crop may make the crop more vulnerable to the impact of an aphid infestation. There is no impact on yield after grain has filled and is maturing (soft-hard dough).

Prolonged infestation can reduce tillering and result in earlier leaf senescence. Controlling aphids generally results in a recovery of the rate of root and shoot development, but there can be a delay.

Late aphid infestations

Infestations that occur during booting to milky dough, particularly where aphids are colonising the flag leaf, stem and ear, result in yield loss. Generally, the distal grains in the head fail to fill. Infestations at this stage in which aphids colonise the leaves, particularly lower in the canopy, tend to result in grain with reduced N (protein) rather than a loss in yield. Aphids are intercepting the N being relocated from leaves to the filling grain.

Article by Melina Miles

Melina, excellent article with some really meaty information. Congrats.

Cheers

Kym Perry