The Department of Agriculture and Fisheries runs pheromone trapping networks as an early warning system for flying pests. Current trapping networks focus on lepidopteran (moth) pests:

- Helicoverpa (H. armigera and H. punctigera)

- Fall armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda)

It is important to note that the primary function of pheromone traps is not to provide definitive counts, but to act as an ‘early warning’ for adult presence. In-crop sampling is required to accurately assess the presence of eggs and juvenile stages.

Pheromone trap

Pheromone traps use chemical signals (pheromones) emitted by females to attract a mate (therefore pheromone traps only catch males of that species). Sorting through large numbers of insects can be extremely time consuming, and pheromone traps have the advantage of being much more specific than pitfall, sticky, or light traps, reducing the number of incidental insects caught.

Although more commonly used in horticulture, pheromone lures are currently commercially available for several pest species that can occur in broadacre crops, including Helicoverpa armigera, Helicoverpa punctigera, fall armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda), diamondback moth (Plutella xylostella), cluster caterpillar (Spodoptera litura), and green mirids (Creontiades dilutes).

In intensive agricultural systems, pheromones have been used as a direct management tool through mass trapping and mating disruption. Note that pheromones are sex-based whereas attract and kill control options (such as Magnet®) are based on combining feeding attractants (such as plant volatiles) and feeding stimulants with insecticide. These are applied in patches or strips within the field to attract flying nectar-feeding adults (such as pest moths), and can attract both males and females.

Pheromone traps can also be useful in biosecurity programs (for exotic pests that have lures available), as there is a greater chance of detection using a pheromone attractant than by routine presence/absence sampling.

Pheromone trap types

The most commonly used pheromone traps in grains in the Northern Region are bucket traps, but delta traps can also be used with pheromone lures. Both trap types are suitable for use in a wide range of crops, easy to set up, and re-usable (except for the single-use delta traps)

- Bucket traps consist of a lid containing the cage that holds the lure above a funnel leading to a holding bucket. The assembled trap is suspected by a wire hanger. The target insect is attracted to the lure, falls through the funnel and into the bucket, where an insecticide-infused cube prevents escapes and minimises damage (making it easier to confirm identification). They are relatively weather-proof and can hold more insects than delta traps.

- Delta traps are tri-folded to create a sheltered triangular area open at each end with a sticky side. They are available as single use, or with a replaceable sticky sheet.

Pros and cons

Traps, unlike in-field sampling, continue to work 24/7. The primary advantage of pheromone traps is they have minimal bycatch compared to other attractant or incidental trapping methods, allowing a faster assessment of target pest numbers.

Pheromone traps can provide general evidence on pest presence, including identifying possible mass immigrations and the potential timing of peak egg lay events. However, results from pheromone traps are indicative only; in-field sampling provides a more accurate picture of pest presence. Side by side pheromone trapping and paddock monitoring for Helicoverpa punctigera has shown no obvious correlation between moth catches in pheromone traps and egg or larval counts in the crops. Pheromone traps are therefore best used as an ‘early warning’ to highlight the presence of adults in the vicinity of the trap, and are particularly useful for detecting migratory influxes or local emergence of diapausing species.

As pheromones are volatile, to maintain efficacy, lures have a recommended ‘use-by’ date. They may have to be replaced during the season and stored in the fridge. Remember also, that you are only catching males, and that moth pheromones are not targeting the lifestage that actually causes damage in the field, so development time needs to be taken into account.

Trapping networks

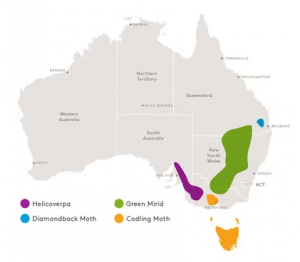

The National Pest Information Network, comprising various State Departments and Cesar Australia service a network of pheromone traps across Australia.

- In the Northern Region, a Helicoverpa trapping network for both armigera and punctigera was active until 2020. The trap catch data from 2015 to 2020 is available in the Beatsheet’s Helicoverpa section. DAF is currently focussing on fall armyworm, with the trap catch results available at the Beatsheet’s FAW section.

- In the Southern Region, Cesar Australia and SARDI report on their native budworm trapping network in the Pest-Facts south-eastern and southern newsletters.

- In the Western Region, DPIRD report on native budworm in their newsletters and on their website.

- National trapping results from the NPIN are also represented visually at MothTrapVis.

Making the link between adults and other life stages.

A prediction can be generated of when larvae may be present in the field by using modelling based on life stage development. DARABUG provides a convenient and readily available means of predicting development times using insect models. It uses gridded climatic data of daily temperatures to generate estimates of occurrence dates for each stage of an insect’s life-cycle. The model currently provides estimates for fall armyworm and Helicoverpa punctigera (native budworm, who’s development times are also applicable to H. armigera).

Setting up your own pheromone traps

Obviously, the most relevant trap results are the ones that are local to your own paddocks. Setting up your own traps is relatively easy. Trap components are sold by multiple suppliers. You will need the lure, a trap (bucket or delta) and relevant accessories (insecticide cube/sticky sheets), mounting wire and something to mount the trap to in the field, such as a star picket (see photo at the top of the page).

The effectiveness of pheromone traps depends on correct placement. To detect local changes in pest abundance, the traps need to be in the field before the pest becomes active or immigration events occur. Also consider factors that may improve capture such as mounting height, proximity to the crop, and the influence of full moon/rain/temperature.

Bio-Trap DDVP (Dichlorvos) cubes can be used with the bucket trap to provide quick and effective knockdown of insects as they enter the trap. These cubes (or strips) are sold as a separate product and are not included when purchasing the trap. It is strongly recommended to use DDVP cubes when monitoring fall armyworm, which has a higher rate of bycatch than helicoverpa. A quick kill helps keep moths intact for identification. Use of DDVP cubes with a fall armyworm pheromone lure is approved by the APVMA under permit PER89169. Traps must be labelled as per the instructions in this permit.

Examples of suppliers (listed in alphabetical order):

- BioLogicalAG — Bucket traps, FAW lures, and insecticide cubes

- Bugs for Bugs — Bucket traps, various pheromone lures and insecticide cubes, as well as a range of beneficial insects.

- EcoKimiko — Bucket traps and green mirid lures

- Entosol — Bucket and delta traps, DDVP strips and helicoverpa lures.

- OCP — Bucket traps and FAW lures.

Delta and bucket traps can also be obtained from many domestic pest companies, however their products usually target household (cockroaches, flies, wasps pantry and wardrobe moths etc, see for example Agrisense traps and lures) rather than agricultural pests.

See the More information section below for more detailed information on setting up the traps and sorting bycatch.

Making the link between adults and other life stages

A prediction can be generated of when larvae may be present in the field by using modelling based on life stage development. DARABUG provides a convenient and readily available means of predicting development times using insect models. It uses gridded climatic data of daily temperatures to generate estimates of occurrence dates for each stage of an insect’s lifecycle. The model currently provides estimates for fall armyworm and Helicoverpa punctigera (native budworm; the development times are also applicable to H. armigera).

More information:

- How to set up and operate helicoverpa pheromone traps (theBeatsheet 700kB PDF)

- (VIDEO) Using a pheromone trap for Helicoverpa monitoring

- Guide to sorting by-catch in FAW pheromone traps (theBeatsheet 1MB PDF)

- (VIDEO) Sorting and processing possible FAW moths

- DPIRD (Western Australia) has also released a fall armyworm surveillance manual with instructions for setting up pheromone traps (12MB PDF).

Disclaimer: Mention of products is for information purposes only. DAF has not evaluated the products sold by each of the suppliers listed. Inclusion here does not imply DAF endorsement and DAF makes no suggestion as to which products are most suitable for trapping under Australian conditions. If you have additions or corrections to the list above, please notify Tonia Grundy (see Entomology contacts).