One of the major contributors to this continuing low pressure is probably the very high natural enemy (beneficial) impact on FAW. A number of very common parasitoids and predators have been observed attacking FAW. Two of the most common natural enemies active in crops are the larval parasitoid wasp Cotesia sp (possibly Cotesia ruficrus) and the spined predatory bug (Oechalia schellenbergii). One of the other common, but more difficult to see, natural enemies is Trichogramma (an egg parasitoid). In north Queensland, Trichogramma egg parasitism has been very common in our trial plots. In north Queensland, particularly on the Atherton Tablelands where it has been very wet recently, the pathogenic fungi Metarhizium rileyi (formerly Nomuraea rileyi) has had a major impact on FAW populations in some crops.

The most commonly observed natural enemies attacking FAW to date: white, fluffy pupal cocoons of the larval parasitoid, Cotesia sp. (left); a FAW egg mass parasitised by Trichogramma – the wasps have emerged through small exit holes (centre). A FAW larva killed by the fungal pathogen Metahrizium rileyi (right). Above right is a spined predatory shield bug making a meal of a FAW larva.

Looking for FAW and distinguishing its damage from helicoverpa damage

It is very likely that both helicoverpa and FAW will be present in most maize and sorghum. Native armyworm species (e.g. common or northern) may also be present in some crops.

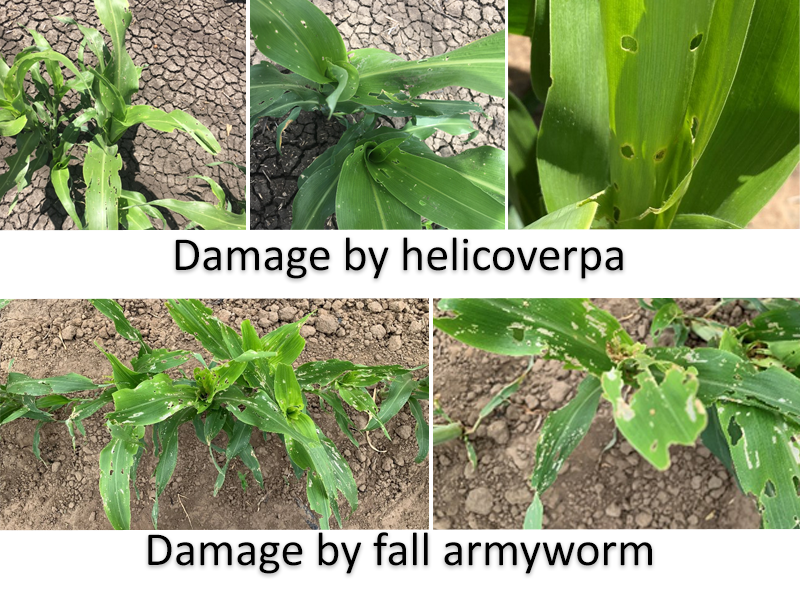

What will be most obvious when FAW are present is the amount of damage that they cause to the leaves. We are used to seeing some windowing from helicoverpa, but largely they do very little damage to the developing whorl. The worst of it is usually ‘shot holes’ in the expanded leaves.

In contrast, FAW larvae feeding in the whorl cause significant damage to the whorl. This will be evident, not only by examining the whorl, but from the large holes in the expanding leaves as a result of the amount of damage caused in the whorl.

Helicoverpa damage to sorghum (top row) tends to be minor windowing, evident in expanded leaves. Whorl appears unaffected (2 photos by Rory Kerlin). Top left: Helicoverpa ‘shotgun holes’ in leaves. FAW damage to sorghum (bottom row) often involves more extensive windowing and damage to the whorl, and large holes are evident as leaves expand.

Side view of FAW damage in sorghum (left) and a plant with very characteristic damage where the terminal end of the whorl has been chewed off, resulting in the whorl and emerging leaves being flat across.

Larvae causing damage in the whorl are generally medium and large larvae. Feeding by very small and small FAW larvae that have recently emerged from eggs is also very recognisable. Feeding by small larvae that are not entrenched in the whorl is similar to that caused by helicoverpa, but more extensive (when pressure is high).

Feeding damage caused by newly hatched FAW larvae – some of the moth scales that covered the egg mass are still visible on the right hand side of the feeding area (left); and windowing caused by small FAW not yet established in the whorl (right).

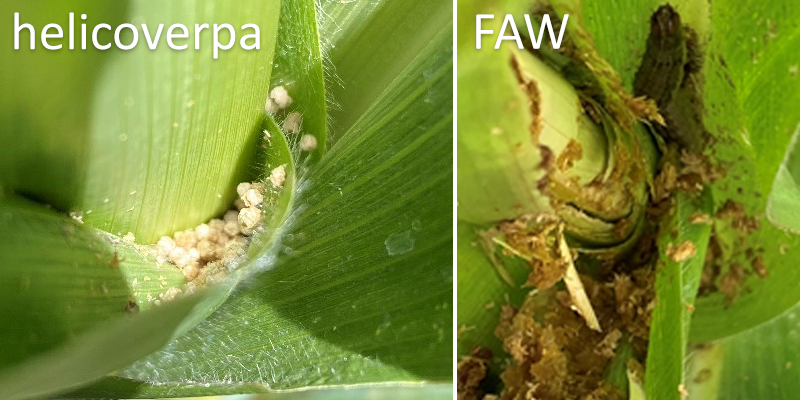

The other thing you will notice with FAW (that you don’t see so much with helicoverpa) is the amount of poo/frass they produce. Huge amounts of it that fills the whorl. It is wet and sloppy, not dry pellets like helicoverpa and native armyworm species.

Helicoverpa poo — lovely and dry (left), and Oh no what a mess!! FAW for sure! (right).

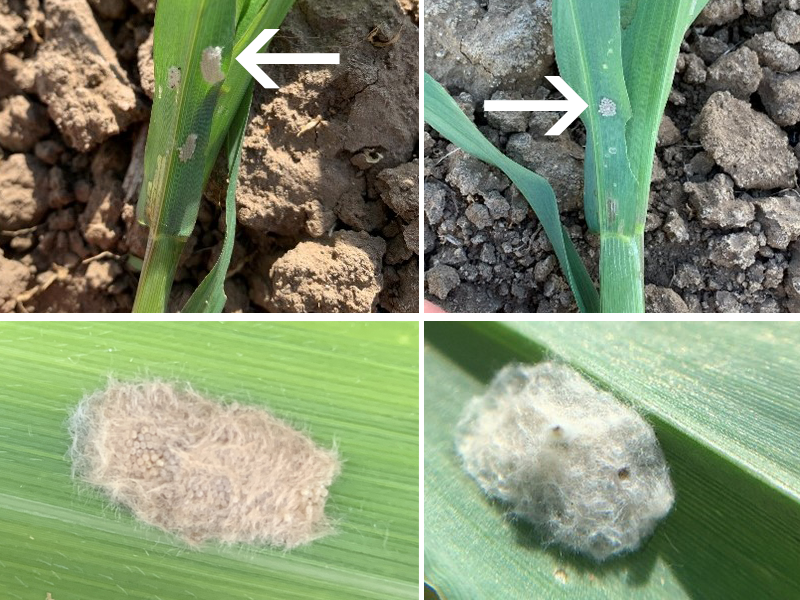

Scouting for eggs can feel like looking for a needle in a haystack. There is so much leaf area in a crop of sorghum or maize. Our experience in north Queensland so far has been that eggs are often laid in about the same place on plants. On small plants, they are often on the undersides of the leaves, towards the base.

Typical location of FAW egg masses on young plants. Note that the layer of scales covering the mass does not always look the same (bottom row).

We have found it a bit easier to find eggs on the underside of leaves if you are checking in the early morning or late afternoon. At these times of the day the eggs on the underside of the leaf can be silhouetted, meaning that you can walk along rows looking for the shadows, rather than turning leaves over constantly.

Viewing the egg masses in silhouette through the leaf can make them easier to see.

Male FAW are more patterned than females (female FAW moth pictured right).

In young crops, FAW do not only feed on leaves. They can also burrow into the base of young plants, resulting in plant death. This may happen when large larvae (which have consumed most of the plant) have to take shelter during the day in the soil. The larvae sit under the soil surface feeding on the base of the seedling plants. For this reason, it is important that emerging crops are check at least weekly. If a high percentage of plants have FAW larvae, and the larvae are medium or larger, there is a risk of this kind of damage. Once plants have 6-8 leaves, there is more leaf and less likelihood of this type of damage occurring.

Large FAW larvae shelter under the soil surface and feed on the base of seedlings (left), and damage caused by this feeding. Larvae can burrow up inside the stem too (right).

Some larval identification basics

FAW and helicoverpa can appear very similar, particularly when larvae are young. Once you have had a bit of experience with FAW, the differences will be more obvious, but until then it is a struggle to work out which is which. Remember, as with all insects and characteristics, there can be significant variation between individuals.

Also keep in mind that the vast majority of helicoverpa that are found in cereal crops (including sorghum and maize) will be Helicoverpa armigera, not H. punctigera.

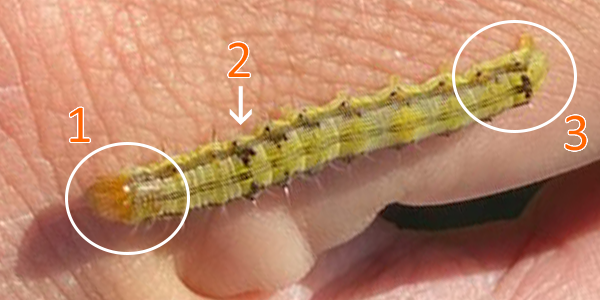

The images below were sent to the Field Crops Entomology team for identification. The annotations have been added to highlight the features used to classify them as helicoverpa or FAW.

- The collar (the narrow shield behind the head) is a different colour to the head, indicating helicoverpa. In FAW, the head and the collar are generally the same colour.

- The ‘saddle’ is visible on this specimen = Helicoverpa armigera

- While the spots at the rear end are arranged in a square, they are the same colour and ‘intensity’ as the spots along the rest of the body. In a FAW larva this size, the spots on the rear are much more prominent.

This FAW larva is a similar growth stage to the helicoverpa above. All the spots on the body are a similar colour and texture at this stage. Third to fourth instar FAW and helicoverpa are difficult to distinguish, so it is worth keeping larvae that you can’t identify easily, with some leaf material, for a couple of days. Over time it will be more obvious which is which.

Again, this is one of the challenging stages. As in the first image, the saddle is visible and the overall impression is of a spikey, rather than plump, larva. The 4 dots at the rear end are not standing out from the others. It is a helicoverpa.

If in doubt whether your larvae are FAW or helicoverpa, please to send photos to Melina Miles ([email protected] or 0407113306) or Hugh Brier ([email protected]).

A Caterpillar identification: taking photos factsheet can be downloaded from the Beatsheet’s FAW ID page.

Photos by Melina Miles unless stated otherwise.

Really nice work Melina and team – this is a very useful guide!