As winter cereals, canola and pulses flower and fill grain, and temperatures rise, the risk of infestation by caterpillar pests increases. Below is a quick refresher on the risk of infestation and crop loss by common caterpillar pests: helicoverpa, native armyworms and fall armyworm.

Key points:

- There is increased risk of infestation by Helicoverpa armigera this spring because of the wetter winter conditions. Check crops through flowering and be particularly vigilant from early grain fill/pod set.

- Native armyworm and fall armyworm may also be present in winter crops. Both are primarily defoliating pests. Whilst head-lopping by native armyworms is a risk, we don’t know what to expect with FAW in later crop stages.

- If damage and/or larvae are observed, correct identification is essential to ensure appropriate management decisions are made. If spraying is warranted, remember that both H. armigera and FAW have resistance to multiple insecticide MoA groups.

Helicoverpa

Helicoverpa species pose the greatest risk to all winter crops. Historically, wetter winter conditions promote higher Helicoverpa armigera activity in spring. Wetter winters are usually associated with warmer conditions and more host plants that support H. armigera populations over winter and in spring. This increases the likelihood of H. armigera infestations in winter cereals during grain filling. The other helicoverpa species (H. punctigera, native budworm) has a strong preference for broadleaf crops and does not tend to infest winter cereals.

Helicoverpa larvae can pose a high risk to maturing winter crops.

Check crops with a sweep net or beat sheet through flowering and particularly from early grain fill/pod set. H. armigera cannot be effectively controlled with synthetic pyrethroids and carbamates, so correct identification is important if treatment is necessary to prevent crop loss. For more information on resistance and the surveillance program, visit the Beatsheet.

This year’s pheromone trap network to monitor spring migrations has only recently been established across Queensland, however previous trapping experience has clearly shown that in some years H. armigera can be active from July. There is always a proportion of the H. armigera population that doesn’t go into diapause, and the survival of this population is likely to be higher in seasons when winter is mild and host plants available. These are the moths that are detected in traps before the emergence of diapausing moths occurs in October – November.

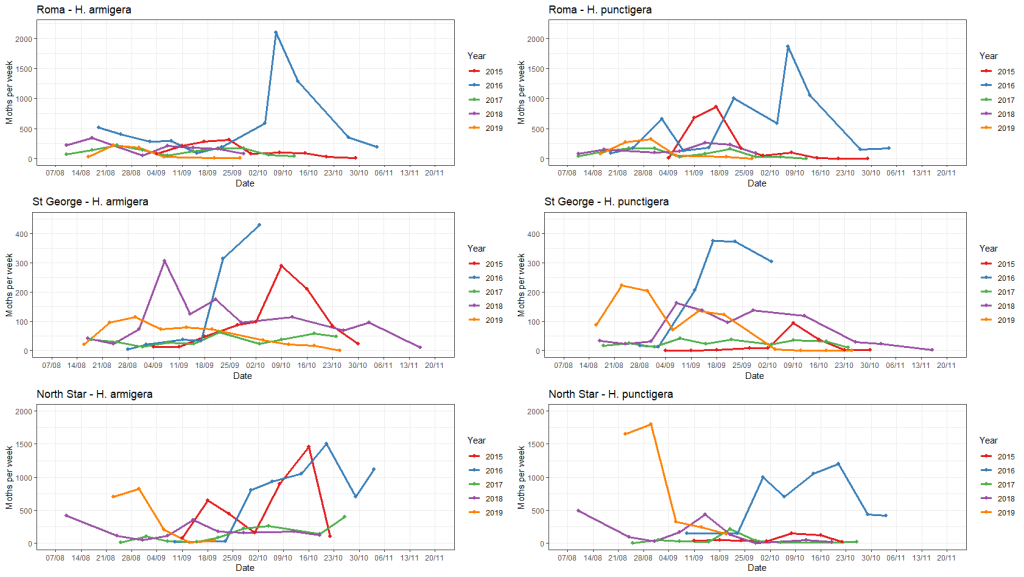

Helicoverpa trap data from 2015-2018 is presented in the figure below, showing how the timing and size of trap catches varies from year to year. In this data set, 2015 (red) and 2016 (blue) had wetter winters through QLD and northern NSW – similar to the 2024 scenario.

Pheromone trap counts over five winter-spring cropping seasons for Roma, St George and North Star (which was moved to nearby Boggabilla in 2019).

For a more in-depth discussion around the role of temperature and rainfall on seasonal Helicoverpa species abundance see the article by Trevor Volp summarising the 2015-2019 trapping results. https://thebeatsheet.com.au/2019-helicoverpa-spp-pheromone-trapping-in-the-northern-grains-region/

Native armyworm species

Native armyworm species have been causing minor defoliation in winter cereals for several weeks.

The most significant risks are associated with high density populations of native armyworm that defoliate the upper canopy prior to flowering and during grain fill. If larvae persist into crop senescence, they may lop heads by feeding on the stalk as the crop canopy dries and foliage becomes unsuitable. While head lopping is a dramatic, it is an uncommon occurrence and regular monitoring is suggested rather than prophylactic treatment of infestations that may complete their development without causing any head lopping.

Native armyworm species from winter cereal showing key features (from left to right): 1. central and lateral white lines immediately behind the head (on the collar); 2. absence of obvious spots along the body; and 3. the smooth, hairless appearance. Photographs courtesy of Richard Fraser.

Use a sweep net or beat sheet to monitor for native armyworm (and helicoverpa) in winter cereals. Scattered frass (insect poo) on the ground can also be an indicator of native armyworm activity.

Armyworm larva and frass (left) and armyworm larvae in a sweep net.

Previous research has identified parasitism (tachinid flies and wasps) as a major cause of mortality in native armyworm populations. One of the most recognisable is Cotesia ruficrus that leaves a cluster of white, fluffy cocoons behind when the parasitoids emerge from medium larvae.

The Cotesia ruficrus parasitoid is gregarious, meaning multiple eggs are laid into an armyworm larva and multiple wasps eventually emerge after pupating in white, fluffy cocoons.

Fall armyworm

Since FAW first arrived in Australia in 2020, we have not seen it infest winter cereals in spring. In February to May this year, we saw infestations of early oats, barley and wheat where some crops were severely defoliated (read the Beatsheet article). In warmer regions (western Downs, Central Queensland), FAW infestations have persisted at low levels in winter cereals for much of winter.

Unfortunately, we haven’t enough experience to predict what FAW activity will be like this spring. FAW has not been reported impacting broadleaf crops (e.g. winter pulses, canola), so at this point we consider the risk of FAW impacting these crops in spring to be low. Even in winter cereals, FAW presence may not result in significant damage. Overseas, FAW damages winter cereals in autumn as they are establishing, but there aren’t reports of post-flowering damage, although northern hemisphere winter conditions will decimate FAW populations. Last summer we saw extremely high FAW activity that persisted in some regions into autumn, and so there is concern that the high end-of-season population might mean that we will see higher FAW activity over the next few months, rather than the low level of activity seen in previous years.

FAW pheromone traps in the Lockyer Valley are catching FAW moths now (August) and there have been low moth numbers throughout winter. These moths are likely to be emerging after having fed as larvae in sorghum or maize crops and then developing slowly through winter as pupae in the ground. FAW does not have a winter diapause like H. armigera, and larvae will continue to develop slowly on available hosts (e.g. maize volunteers) until they are ready to pupate. Whatever the starting population is, it will still be smaller, and pose less risk to susceptible crops than populations that are expected through December – March.

When monitoring for helicoverpa, examine larvae to determine if there are FAW present and if you are finding FAW in cereals, let DAF entomologists know.

Who am I?

In July there were reports of fall armyworm infesting winter cereals in the South Burnett, but given the crop stage and winter conditions, the caterpillars are also possibly H. armigera. The larva in the social media photograph below (on a post that urged growers to monitor for fall armyworm) looks to have the ‘saddle’ (of darker pigment on the 4th segment) that is a characteristic of medium H. armigera and separates this species from H. punctigera and FAW (for more detailed information on identifying the different species see the Beatsheet’s helicoverpa page.

A recent alert on social media recommended growers monitor for FAW in barley. The image, which also appears to have helicoverpa characteristics, indicates how difficult it can be to tell caterpillar species apart.

Tips to improve your chances of correctly identifying larvae

Descriptions of some of our common caterpillar pests often include similar characteristics, particularly when young, and the inherent variability of some species compounds the problem. It is a good idea to carry a container with you to collect the caterpillar(s) to give you a chance for a closer examination later (or if you have time, rear to a larger size, when characteristics are more obvious).

If in doubt, take photos and send them through to DAF’s Entomology team for identification. Photos need to be good quality and in focus, and clearly show the specimen from several angles so that features used in identification can be seen.

Download the instruction sheet on Caterpillar identification – taking photos that show key characteristics (600 kB PDF) that includes example illustrations.