After the introduction of Bt cotton in the 1990s, the focus of cotton pest management has shifted to sucking pests.

Green and brown mirid (Creontiades spp.) damage can occur at any stage, from seedling to boll filling, although crops are usually attacked before peak flowering. Feeding damage (including terminal death, abscission of young squares and bolls, and lint damage in developing bolls) can result in significant yield loss. Mirids are therefore often the target of early and mid-season insecticide applications which, in turn, can result in the disruption of the beneficial insect community in cotton crops and flaring of secondary pests such as mites, whiteflies and mealybugs.

A key component of mirid IPM in cotton has been the development and use of economic thresholds (ETs). First published in the Cotton Pest Management Guide 2005-06, the mirid management guidelines for Bollgard cotton featured ETs appropriate for different climatic regions, crop stages, sampling methods and levels of crop damage.

However, adoption of these thresholds was highly variable and production practice surveys indicated a lack of confidence in them, with frequent reports of more crop damage and fruit loss than expected based on mirid densities found in the crop. These survey findings, along with productivity gains and yield improvements in cotton production systems in Australia over the last decade led to a review of mirid management and thresholds.

Economic thresholds for controlling mirids in Australian cotton crops up to 2018. These have been reviewed and the updated thresholds published in the 2018-19 Cotton Pest Management Guide.

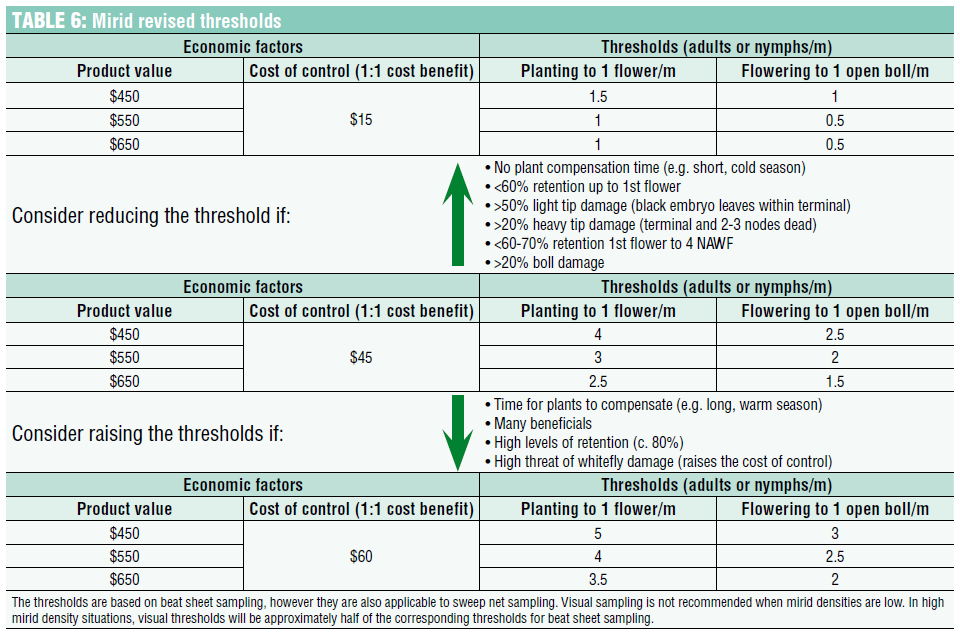

Crop damage can vary significantly between growth stages, and yield loss is influenced by the plant’s capacity to compensate (dependent on crop management, the stage when damage occurs and climatic conditions). While the original mirid ETs included this, the level of mirid damage and the economics that underpinned them reflected cotton production systems of the early to mid-2000s. The revised thresholds (see figure below) account for today’s high yielding crops and the increasingly complex economics of mirid management.

ETs are based on a cost-benefit ratio greater than 1 (i.e. economic loss from not controlling the pest is greater than the cost of control), but mirid control is sometimes justified a lower ratios because of the risk of cumulative damage, particularly at times when the crop is unlikely to be able to compensate. While an ET is usually determined by the cost of control, the value of the product and a damage parameter, consideration should also be given to costs that may arise in later crop stages as a result of the decision to spray now, such as additional sprays for flared pests.

The old ETs were based on a fixed control cost ($15/ha) and product value ($450/bale) with damage estimated per mirid per ha per day. Today, given the higher costs of selective, IPM-compatible insecticidal products now available for mirid control and relatively high cotton prices, the ETs have been recalculated with a range of control costs and product values.

Revised economic thresholds and associated guidelines for controlling mirids (2018-19 Cotton Pest Management Guide).

The new guidelines don’t include adjustments for climatic regions because industry feedback indicated that it was not particularly useful. Instead, crop managers are urged to use local knowledge of crop growth, season length and climatic conditions, along with the plants’ ability to compensate for fruit loss. Depending on crop stage when damage occurs, greater economic impact is often seen in shorter season production environments (limited water may also impact a crop’s ability to compensate).

A mismatch in crop management (checked twice-weekly) and ET time scales (calculated daily) has been eliminated by computing the revised ETs in the same time units as crop checking. Note that both sets of thresholds are equivalent from a damage perspective – the new version just provides more economic context on which to base spray decisions.

Crop managers should always balance the risk of damage against the true cost of mirid sprays. This includes not only the upfront (product + application) costs, but also the cost of additional sprays for mirids if repeated intervention is required and/or costs arising from disruption of beneficial insects and consequent flaring of other pests such as silverleaf whitefly and mealybugs. There is considerable evidence to indicate that the cheapest product is seldom the most economical and IPM-friendly option over the life of the crop.

Often overlooked in mirid spray decisions is sampling accuracy, which is critical for making well-informed and timely spray decisions. A typical sampling regime of 2-4 beatsheets per check per 50 ha is usually inadequate and could under or overestimate mirid density in the crop by 50% or more. Note that mirids move quickly, particularly in hot weather, making them hard to count and compounding the accuracy problem. While these thresholds are based on beat sheet sampling, they are also applicable to sweep net sampling, but need to be halved for visual sampling. Visual sampling is not recommended for low mirid densities.

Future research will focus on fruit production/loss in Bollgard 3 varieties in relation to weather, pests, crop management and intrinsic plant factors.

Refer to the new mirid management guidelines (see 2018-19 Cotton Pest Management Guide, available from the CottonInfo website) for more information on the revised mirid management guidelines and thresholds, sampling requirements, and ways to improve confidence in pest density estimates.

Article edited by Tonia Grundy. Based on research by Richard Sequeira, DAF Emerald & Mary Whitehouse, CSIRO Narrabri.

This research has been supported by CRDC. The project was reported in more detail in the September 2018 edition of the Australian Cotton Grower.