Fall armyworm (FAW, Spodoptera frugiperda) is an exotic pest that was detected in northern Queensland in a maize crop in February 2020. State and federal biosecurity organisations have determined it to be unfeasible to eradicate this pest and it is now classified as an endemic pest.

Originating from tropical and sub-tropical areas of the Americas, FAW was reported in Africa in 2016 and has subsequently spread across much of Africa and southern Asia. Crops recorded as preferred hosts of this pest in other regions include maize, sweet corn, rice, sorghum, cotton and sugarcane, along with many horticultural species.

In partnership with industry, staff at the Department of Agriculture and Fisheries will be conducting research to understand the pest status of this insect within our production systems with the aim of identifying and developing a range of sustainable practices (cultural, biological and chemical) to enable effective control.

Insecticide resistance has been a feature of FAW infestations with almost complete failure of all options in Brazil causing significant management issues. Insecticide resistance management of this pest, and the consideration of how its management will impact on resistance development in Helicoverpa armigera and other species will be a key focus of research.

In the interim, Industry bodies are collaborating to secure emergency permits to provide growers with chemical management options should control be required.

It is possible that FAW infestations will be severe in the first few years of this incursion. This has been the pattern for other exotic species in recent years (e.g. silverleaf whitefly outbreak in CQ and solenopsis mealybug). As industries become more confident and experienced in managing this pest, and natural enemies start to suppress outbreaks, FAW is likely to become more easily managed in our farming systems.

How can I tell it’s FAW?

At a glance, FAW larvae look similar to other armyworm species and other caterpillars that grow to a similar size (3-4cm), such as helicoverpa and cutworms. Larger FAW larvae can be identified by the presence of a prominent set of four raised spots on their second last body segment.

- Fall armyworm

- Common armyworm

- Dayfeeding armyworm

- Helicoverpa

- Cutworm

- Cluster caterpillar

FAW lifestages

- FAW eggs

- FAW larva

- FAW larva

Above: egg mass and two colour variants (2)

The pale yellow eggs are laid in ‘furry’ clusters of 100-200.

As larvae develop, they become darker with white lengthwise stripes and develop dark spots with spines. Older larvae have an inverted ‘Y’ shape on the head and a distinctive pattern of four dark spots on the second to last body segment. Larve can grow to up to 40mm long.

The red-brown pupa is found in soil under the host plant.

Adult moths have a brown or grey forewing, a white hind wing, and a wingspan of 32–40 mm. Male fall armyworms are more patterned and have a distinct white spot on each forewing.

Fall armyworm take about 2-3 weeks to develop from egg to pupae (depending on temperature), and another 2-3 weeks before moths emerge.

Fall armyworm characteristics include the inverted ‘Y’ on head capsule and four raised spots in a square at the rear (1)

Typical damage symptoms

FAW damage in many crops is similar to that caused by other caterpillars. If you find damage symptoms, carefully examine the plants for larvae to identify which species are present.

Spodoptera commonly cause ‘windowing’ on the leaves.

FAW can cause chewing damage to leaves, whorls and reproductive structures similar to that of helicoverpa

What will this detection mean for broadacre crops in the northern Grains region?

At this early stage, it is difficult to know how significant a pest fall armyworm will be in different crops and regions. It is likely that persistent populations will occur from Central Qld north, with annual (or sporadic) migrations further south. Populations will not survive where temperatures go below 10℃, and there are frosts. Northern Australia (tropical and subtropical) areas are likely to host populations in crops, pastures and weeds/native grasses.

In the United States, FAW is most common in the southern (warmer) states of Texas and Florida with northern occurrences confined to migrations during late summer and early autumn. How Australia’s climatic and vegetation zones will influence the timing and magnitude of migrations is difficult to predict.

What crops are at risk?

Maize (and sweet corn)

Maize (corn) is a highly preferred host of FAW and therefore has a relatively high risk of crop losses. Sweet corn is even more high risk because of low market tolerance for damaged cobs. In maize, larvae feed on the leaves, creating ‘windows’ (irregular, elongated holes). Larger larvae establish themselves in the whorl where they can damage the growing point, and larvae can also feed on reproductive structures as they develop. Moths may also shelter in the whorl during the day. Where heavy infestations occur, frass (insect poo) will be visible on leaves and in the whorl. If damage is evident, but larvae is not visible in the foliage, check in the whorl.

Maize can be attacked at all growth stages, so crops need to be checked regularly up to maturity. Rapidly growing plants can tolerate some defoliation in the vegetative stage, but significant loss of leaf between V6-R1 will impact on growth and yield. Damage to cobs during grain filling can also impact on directly on yield, and on grain quality through allowing entry of fungi and bacteria.

Damage to leaves, the whorl and cobs, looks similar to the damage caused by Helicoverpa armigera, common armyworm (Mythimna convecta) and cluster caterpillar (Spodoptera litura). Cluster caterpillar have been observed laying on the lower leaves and small larvae ‘windowing’ these leaves before moving up on maize plants (see images above). FAW can also sever seedling maize plants at the base, similar to cutworm damage. It is advisable to open the whorl and carefully examine larvae found during sampling to determine which species are present.

FAW is not susceptible to helicoverpa NPV used to control H. armigera in maize and sweet corn. It is, at this point, unclear whether FAW is susceptible to Bt products.

Sorghum

Monitor for FAW in sorghum in the same way you would monitor for Helicoverpa armigera, but also check regularly during establishment and vegetative stages for defoliation, particularly on lower leaves where eggs and early instar larvae may be concentrated.

Younger sorghum plants are damaged by FAW, but this damage does not usually impact on plant growth and yield, unless pest pressure is high and defoliation severe.

FAW typically infest the whorl of sorghum plants, resulting in emerging leaves having large, irregular-shaped holes. Helicoverpa armigera and other armyworm species will cause the same type of damage in sorghum, so it is important to open the whorl up to identify the larvae.

FAW will move onto heads as they emerge. Check for large larvae that will cause significant damage to developing grain.

In the US, control is recommended if damage results in more than 30% defoliation, or there are 1-2 larvae per whorl.

As the panicle emerges, FAW can infest the head and damage the developing grain. Like H. armigera, small FAW larvae feed on the pollen and larger larvae feed on the developing grain. Managing infestations of FAW before heads emerge will reduce the risk of this type of damage.

In Texas, the damage potential of H. armigera and FAW on panicles is considered equivalent. In the event of FAW infestations of sorghum at grain fill, use the Beatsheet’s helicoverpa economic threshold calculator.

FAW is not susceptible to helicoverpa NPV used to control H. armigera in sorghum.

Cotton

Whilst not registered for the control of Spodoptera spp., the Bollgard 3 varieties widely grown are expected to provide some incidental suppression of this pest. FAW incidence may be similar to the native cluster caterpillar, Spodoptera litura which can cause limited damage to tropical cotton crops in some seasons.

Pastures

FAW is reported to feed on C4 grasses in grazing systems overseas. It is likely that tropical and subtropical pastures will support large populations of FAW in suitable seasons. It is unclear what impact FAW might have on the productivity of pastures, but outbreaks of dayfeeding armyworm (Spodoptera exempta) have caused significant short-term defoliation in buffel pastures. This defoliation can kill seedling plants and retard the growth of established plants. Infested pasture may be reinfested by a second generation of caterpillars, offspring of the first infestation.

Small larvae, and their damage, can be easily missed. The majority of feeding is done over about 4 days by the oldest larvae, so defoliation can appear to happen suddenly. Use a sweep net or sweep a bucket through the grass to dislodge larvae. Larvae may be active during the day in thick stands, but more often at night in less dense, or damaged areas. Once all foliage has been removed, FAW will move en masse to a new area.

In the US, 2-3 larvae per square foot, in hay production fields warrants controls. However, the use of insecticides in pastures has to be carefully considered, and may not be viable. Residues in pasture and subsequently in meat are a potential risk, with export slaughter intervals being significantly longer than withholding periods on the labels.

Whilst potentially hosting FAW, pastures are also likely to be a valuable source of natural enemies which will, in time, suppress the FAW populations in these systems.

Dayfeeding armyworm and damage to buffel pastures

How can I manage an outbreak?

There are currently no locally derived thresholds to guide management of fall armyworm due to lack of time to assess the impact on crops in Australia.

Late season crops may experience higher pest pressure as the FAW population builds up during the season. Natural enemies, including egg and larval parasitoids and predators, are likely to be important in supressing FAW populations in crops and pastures. FAW is in the same family (Noctuidae) as many other lepidopteran pests of field crops e.g. loopers, helicoverpa, cutworm, armyworm. All these pests are attacked by various egg, larval and pupal parasitoids, predators, and diseases. It is highly likely that, in time, we will see these natural enemies start to attack FAW as well.

Where chemical interven

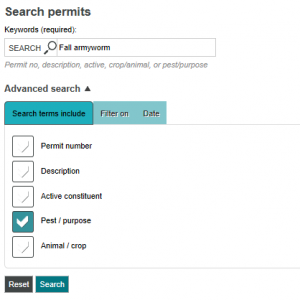

Currently, permit PER88638 has been issued for control of FAW in a range of grains crops. Download from the APVMA.

Permits for other crops are expected to be available soon as approvals are granted. Search for ‘fall armyworm’ and check the pest/purpose button at APVMA’s permits portal.

As fall armyworm pheromone traps become available to industry, they will be a useful early warning of local moth activity and seasonal risk to crops.

What else should I do?

Good farm biosecurity practices include awareness of what is happening on your fields and farm, and reporting any unusual symptoms or concerns. Controlling weeds, volunteer cotton or ratoon cotton plants in fallow fields or in areas around the field, shed and fence lines to reduce the number of host plants available for pest populations to establish and build is also recommended.

If you suspect fall armyworm, notice abnormally high amounts of leaf damage in your crop, or experience a sudden and unexplained fall in production, report immediately to your agronomist or contact the Department of Agriculture and Fisheries Queensland on 13 25 23

More information

For more information, contact the Department of Agriculture and Fisheries on 13 25 23 or visit the Business Queensland website.

Fall armyworm insect images courtesy of Bugwood.org:

- Russ Ottens, University of Georgia

- John C. French Sr., Retired, Universities: Auburn, GA, Clemson and U of MO

Other caterpillars and symptom images by the Department of Agriculture and Fisheries.