The tiny wasp Eretmocerus hayati is an important natural enemy of silverleaf whitefly (SLW) and contributes to the natural biological control of this pest throughout the season. It occurs in almost all regions that grow cotton, but due to its small size (difficult to see without a hand lens) it often goes unnoticed. Like all natural enemies, Eretmocerus is susceptible to insecticides applied to control pest species.

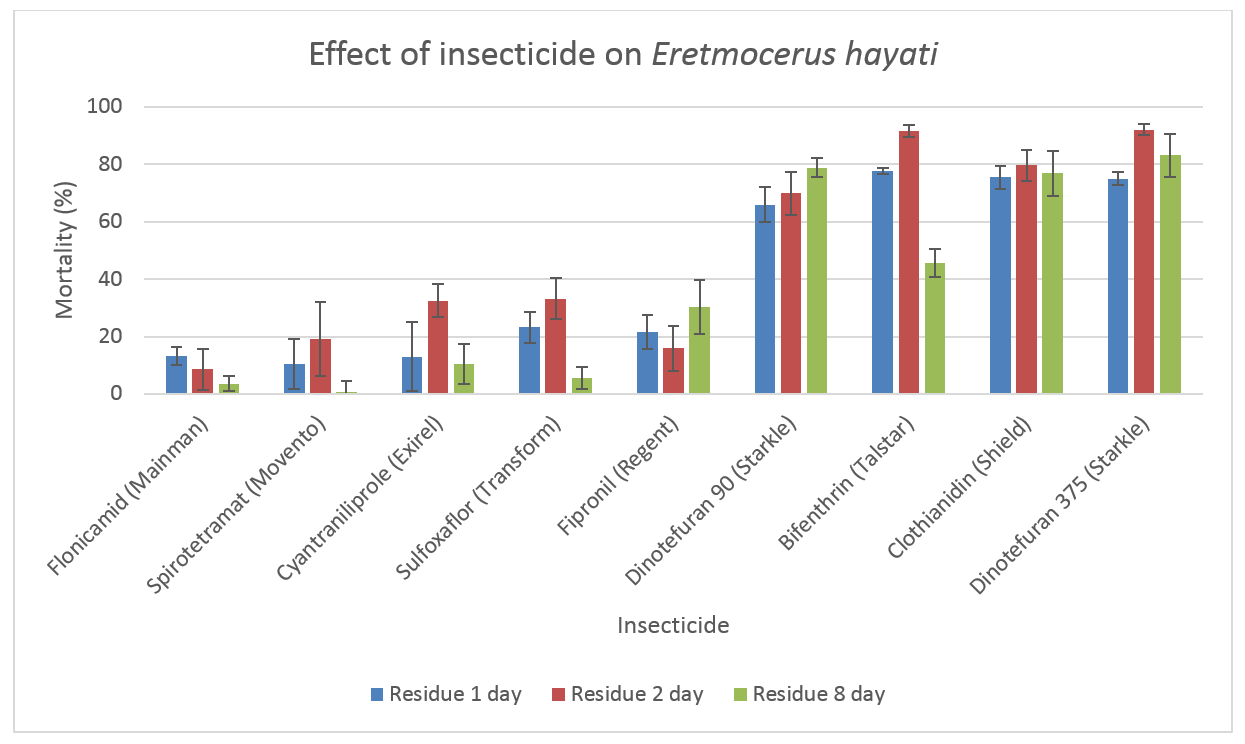

Recently the toxicity of seven products, including recently registered insecticides; cyantraniliprole (Exirel®), flonicamid (Mainman®), dinotefuran (Starkle®) and sulfoxaflor (Transform™) were studied under laboratory conditions.

Spirotetramat (Movento®) and bifenthrin (Talstar®) were included for comparative purposes as their impacts have been previously published and allowed us to rank the impact of the newer insecticides against these known standards.

The study looked at the effect of dried insecticide residues at one, two and eight days after application.

- spirotetramat, flonicamid and cyantraniliprole had low toxicity

- sulfoxaflor (72 g ai/ha), fipronil (12.5 g ai/ha) were moderately toxic

- bifenthrin, clothianidin and dinotefuran were very toxic.

This latest research has been used to update the Cotton Pest Management Guide (available from the CottonInfo website), and can now be used by agronomists to make more effective IPM control decisions throughout the season.

Parasitism levels in the field

During the 2016/17 cotton season we provided a parasitism level assessment service. The number of samples submitted was relatively low for most regions, but indicate that overall parasitism during the season was low in most regions (Table 1), compared to previous years (see previous Beatsheet article How to check for parasitism in whitefly populations). A possible reason for the lower levels of parasitism is the still common use of very disruptive insecticides, including pyrethroids, organophosphates and some neonicotinoids. But even frequent exposure to moderately disruptive chemistry will cause a decline in natural enemy abundance, including SLW parasitoids.

This season parasitism made a significant contribution to the suppression of SLW populations at both locations sampled on the Darling Downs (19.5% and 47%), indicating the SLW populations were in decline and providing some reassurance that control actions weren’t required. The other two samples that recorded high parasitism were either collected very late in the season (where parasitoid populations had time to recover from insecticide exposure–anecdotal reports were that parasitism was low in Moree throughout the growing season), or collected from late-planted crops after earlier-planted crops had been harvested (possibly reflecting timely migration from harvested crops into late planted crops with well-established SLW populations).

Table 1. Average levels of parasitism recorded in parasitism collections 2016/17

| Site | Parasitism (%) | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Emerald | 60 (n=1) | collected from later planted crop after earlier planted crops harvested |

| Goondiwindi | 5.5 (n=10) | |

| St George | 6.5 (n=2) | |

| Darling Downs | 33.3 (n=2) | |

| Hillston | 4.9 (n=1) | |

| Moree | 20.4 (n=1)* | very late season collection |

| Wee Waa | 3.0 (n=11) |